updated on May 9th, 2019

War and dark tourism has been around for centuries. Call it a mix of schadenfreude and morbid curiosity. We humans, myself definitely included, struggle to look away from a good trainwreck, but this is nothing new.

In early warfront record, artists and reporters were seen as tourists to those involved in battle. Some of the earliest war tourists include Wilem van de Velde, who in 1653 went to sea in a small boat so that he could sketch the final naval battle between the Dutch and English in the Battle of Scheveningen.

His artistic talent (and large huevos) would aid him in becoming the official artist of the Dutch fleet. He continued sketching war conflicts like the Four Days Battle and the St. James Day Battle of 1666. Willem and other documentarians were seeking out war time travel personally, it wasn’t until 1854 that war tourism took a commercial turn.

Acting as one of the earliest travel agents, Henry Gaze took his travel party to Brussels to visit the battlefield of Waterloo. Similarly, Workmen’s Travel and the Polytechnic Touring Association scheduled their inaugural tours to the Waterloo battlefield. Although travels were originally based on educational grounds, tours to Waterloo quickly grew as a tourist attraction. Charlatans and swindlers with hazy morals moved in to capitalize on the growing location’s popularity. With fabricated personal tales of battle they sold souvenirs and relics, with stories that tied them to the war engagement. These pieces were purchased in troves, although they were rarely authentic.

We’ve barely skimmed the surface. There has always been a profit to be made from war tourism, including profit that is not monetary. Well-known figures and dignitaries found themselves in a unique situation, being able to provide tourists with an up-close look at battle. The Prince of the Russian Empire, Alexander Danilovich Menshikov, invited the ladies of Sevastopol to watch the Battle of Alma from a nearby hill in 1854. If you’re not familiar with this battle, let us inform you: he actually invited the local good-looking society women to watch the downfall of their livelihood with him. And they attended! Though it’s not all bad. Notably, Mark Twain led tourists to the ruined city of Sebastopol after the Crimean War in Europe. Reports exist of him scolding his travelers for attempting to walk off with shrapnel as souvenirs.

Thomas Cook expanded dark tourism in the mid 1800s to include the spectacle of public executions. His travel agency worked in cooperation with rail companies to help promote the popularity of travel by train. Although Mr. Cook already ran a successful “regular” tourism agency, he began to organize special train excursions which transported passengers to witness public hangings around England. The ambiance of these events had a “carnival-like” atmosphere like most open-air festivals of the time. Executions were marked by high spirits and hefty appetites. Sellers of fried fish, hot pies, fruit, and ginger beer were in high demand, as did hawkers of mournful odes and fake condemned-cell confessions – known in the business as “lamentations.”

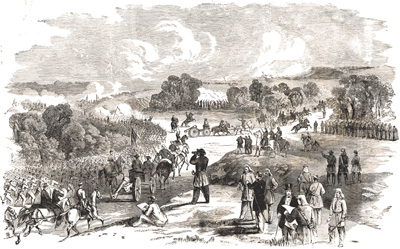

Wartime and dark curiosity was not limited to European geography. During the first major land battle of the American Civil War, many of the wealthy elite of nearby Washington packed picnic baskets and trekked to watch the First Battle of Bull Run (with ghastly consequences). Our old friend Thomas Cook promoted tours of the Second Boer War in Swaziland South Africa before the conflict had even ended. War tourism unsurprisingly was gaining a lot of criticism but also grew quickly in popularity by the end of the 1800s.

Through World War I, it was evident that the related battlefields were becoming popular tourist destinations. French authorities were not keen on the idea. While instances of post-Great War tourism was present, the French limited much of the documentation. Stories of trophy hunting were spun through the media of the time as tales of pilgrimages, rather than being labeled as morbid rubbernecking, which is closer to the truth.

Also during WWI, British intelligence officer Hugh Pollard described Ypres Salient (an area around Belgium where some of the largest battles of World War I took place) as a holy ground due to the great number of Entente (Allies’) graves in the region. Veterans sympathized with his words. Catholic and Anglican tourism quickly became intertwined with war tourism when 100,000 former Catholic servicemen from either side of the conflict paid visit to Lourdes, France to pray for peace.

Today, after WWII and The Vietnam War, tourists flock to destinations of famous battles. Locations of historical significance are supremely popular. We flock to former Nazi concentration camps, the now serene beaches of D-Day, and picturesque Vietnamese and Cambodian countrysides all to reflect on the present and the landscape of our past.

“Both the pilgrim and the tourist engage in ‘worship’ of shrines which are sacred, albeit in different ways, and as a result gain some kind of uplifting experience.”

John Urry, a British sociologist and Professor at Lancaster University has said that “both the pilgrim and the tourist engage in ‘worship’ of shrines which are sacred, albeit in different ways, and as a result gain some kind of uplifting experience.” Essentially, no matter the motivation, both groups are attracted to “gaze” upon a “sacred object”of hallowed ground.

While we’ve examined the genesis of war tours and dark tourism, what is to be said of the current state of this less common tourism niche? We are admittedly, to some degree, dark tourists. We recently visited Chernobyl and fully understood the fascination with dark tourism.